Tweet

In my last blog post, "

The Rapidly Diminishing Authenticity of Social Media Marketing," I explored how social media professionals have turned to tactics that undermine some of the core tenets promised by social media. We set larger fan counts as a goal above authentic advocacy, and when meaningful engagement became difficult to achieve, we settled for anything that would earn a like, reply or retweet rather than striving for content that fostered relationships and created value.

I will not rehash how I think these poor priorities and tactics undermined brand success in social media. (You can read my last blog post for that.) Instead, I want to explore a more sensitive question: Have social media marketers acted ethically or not?

For example, if we accept that a basic principle of social media is that "likes" represented something important--authentic brand affinity that others would see and rely upon--then what are we to think of those marketers and brands that took shortcuts to accumulate new fans who had no established relationship with the brand? Was it ethical to launch sweepstakes, contests and giveaways that motivated "likes" from people who otherwise were not inclined to express affinity for our brands?

And if we further agree that engagement such as replies, retweets and shares ought to be authentic signals of interest in what brands have to say, then are we acting ethically when we solicit engagement merely to

elevate our brands' EdgeRank? Is asking Facebook users to "like" a post if they are on "team peanut butter" an ethical way to collect signals of affinity between consumer and brand, or is this a dishonest way to get our content into more users' news feeds?

Social Media Ethics on Display (or Not) During Week of Boston Marathon Tragedy

Instead of considering this in the abstract, let's examine two brands' actions last week, during the frightening events in Boston. NBC Bay Area posted a photo of a young bombing victim and implored people to "'Like' this to wish him a continued speedy recovery." This desperate attempt to trade on people's feelings for a young victim of the bombing in order to receive a bit of EdgeRank-building engagement is horrifyingly unethical, in my book. (And if you do not agree, then please tell me how "liking" an NBC post lends support to or otherwise helps this poor hospitalized child.)

Ford, a brand I praised for authenticity in my last blog post, waded into dubious water with a Facebook status update following the capture of the second bombing suspect. The brand said, "To the first responders of Boston: Thank you. You are true American heroes." Nothing wrong with that--in fact, I love that a brand like Ford feels it can express sincere appreciation for the sacrifices of those who serve. The problem was that Ford didn't post that as text but included it within a beauty shot of their products, complete with the Ford logo and tagline.

Not everyone will agree, but I feel that Ford's use of brand imagery not only reduced the sincerity of the message but demonstrated questionable ethics. Before you disagree, I would ask you to view the two status updates below--one Ford could have posted and the other it actually did--and consider three questions:

- Which is a more authentic expression of appreciation to people who sacrificed their safety to protect us?

- What does the product and brand imagery of the post on the right add (if anything) to the sincerity of the gratitude compared to the simple text version?

- Which version more clearly puts the focus on the heroes in Boston?

|

| The version on the left imagines what Ford could have posted as text while the one on the right is what Ford actually posted following the capture of the second bombing suspect in Watertown, MA. |

Issues of ethics are difficult to discuss. They often are not clear cut, and while it is easy to see when a company crosses the line with both feet (as did NBC Bay Area), it can tough to discern as brands toe the gray line (as did Ford, in my opinion).

It is even tougher to see when you yourself cross ethical lines. If your boss wants to know why your brand has half a million customers but only 25,000 fans on Facebook, a sweepstakes to accumulate fans may not seem unethical. Your perspective may change, however, if you put yourself on the other side of this equation; if you do not want to see your friends becoming shills for brands in return for freebies and giveaways, then your brand should not follow this path. It is unethical to treat your own customers in a way you would not appreciate from the brands you buy or the people you know. (Fifty years ago, David Ogilvy, the father of modern advertising, expressed the same sentiment when he said, "Never write an advertisement which you wouldn’t want your family to read. You wouldn’t tell lies to your own wife. Don’t tell them to mine.")

We are roughly five years into the social media era, and I think perhaps it is time to reset our moral compasses, not to save our souls but to improve business results.

Study after study demonstrate that consumers want something more from brands than silly images and memes; they want ethical behaviors and communications. The 2012 Edelman Trust Barometer Study found that customers increasingly expect brands to "place customers ahead of profits and have ethical business practices," and Interbrand's 2012 brand study noted that "Consumers... want to feel that the brands they love are, in fact, worthy of that love."

I'd like to believe this is always the case in every business situation, but when it comes to social media marketing, the ethical path also happens to be the best one for enhancing brands and business results. How can we improve both the ethics of social media marketing and our brands? Here are three steps:

STEP ONE: Understand Long-Standing Marketing Ethics, Advertising Rules and Regulation

"Those that fail to learn from history, are doomed to repeat it".

- Winston Churchill

I am frequently disappointed to find social media professionals who do not understand the basics of ethics and regulation in the advertising industry. Marketing has a long and well established history of recognizing and enforcing ethical practices, and government regulation of advertising is over one hundred years old. The issues we struggle with today in social media marketing are not new, nor are the core beliefs of ethical marketing. The latter can inform the former for those who care to learn history.

In 1911, the Associated Advertising Clubs issued the Ten Commandments of ethical advertising, and the first Commandment was unequivocal: "Thou shalt have no other gods in advertising but

truth." (The italics are theirs, not mine.) Shortly thereafter, the Postal Act of 1912 required that advertising content be differentiated from editorial content. Together, these two actions established one of the most basic tenets of advertising ethics: That consumers must know when they are seeing advertising and not mistake it for editorial content. This is as true in the pages of newspapers as in the tweets and posts of your customers.

Although the core principles of ethical advertising have not changed in one hundred years, the regulatory language has evolved with technology. In 2009, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) issued "Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising." This document established that "When there exists a connection between the endorser and the seller of the advertised product that might materially affect the weight or credibility of the endorsement, such connection must be fully disclosed." In other words, if it would impact a person's perception of a friend's post about a brand to know that the individual was posting in exchange for a contest entry or a giveaway, that creates a material connection that must be disclosed.

Just last month, the FTC updated disclosure guidelines, providing quite detailed guidance. For example, the FTC notes that "#spon" is not a sufficient disclosure of a sponsored tweet since, "Consumers might not understand that '#spon' means that the message was sponsored by an advertiser." And to those who might protest that Twitter's 140-character limit does not provide sufficient room for a clear and conspicuous disclosure, the FTC says, "Tough luck." (Really, what the agency says is, "If a particular platform does not provide an opportunity to make clear and conspicuous disclosures, then that platform should not be used to disseminate advertisements that require disclosures.")

An understanding of the history of advertising ethics and FTC regulations is only the start. The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) has issued several decisions pertaining to social media that

brands' must consider for their social media guidelines, monitoring policies and employment practices. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has oversight into how and when social media may be used to share information pertinent to investors. Different states have enacted laws with varied requirements for consumer and employee privacy in social media. And then there are the terms and conditions of the social networks themselves, which define what is and is not permissible. (It is shocking how often pages violate Facebook's Promotions rules as defined in the Facebook Pages Terms.)

In the relatively brief period since social media's birth, brands have been tripped up by a variety of unethical and unlawful behavior including meddling with competitors Wikipedia entries, fake community groups, fake endorsements, fake blogs, fake accounts, and other questionable activities. It is vital social media professionals know the laws, rules and ethical standards that have stood the test of time, and it is necessary for marketing leaders to ensure their social media teams are adequately trained and supervised.

STEP TWO: Improve Social Media Metrics

“Not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts”

- Albert Einstein

Bad metrics lead to bad strategies. More than that, bad metrics can lead to unethical behaviors.

The Great Recession of 2009 was caused by many factors, but President Obama laid blame on the way executives were measured and compensated. He noted in a June 2009 speech that a "culture of irresponsibility" was an important cause of the crisis, and he criticized executive compensation that "rewarded recklessness rather than responsibility."

In some ways, many social media professionals are today being rewarded for recklessness rather than responsibility. Fans and engagement are not business metrics, but these are common line items on many social media scorecards and are used by social media agencies and vendors to validate performance. Any brand can count new fans, but how many are measuring the value delivered to the brand via social media? Instead of turning to the metrics that are easiest to collect, social media marketers must determine the metrics that best validate that their social media investments deliver upon the objectives (and if one of your goals is merely to collect fans, then the problem is not the metric but the goal).

This is the point in the blog post when I am supposed to furnish an easy answer for how to measure social media success; unfortunately, I cannot. The ways to measure success are as diverse as brands, audiences and corporate objectives. If you want to better educate your customers on your products, measure that. If you need to raise awareness, measure that. If increasing inbound traffic to your site is desired, measure it. If your brand is challenged to improve a particular perception attribute, then that is what you should measure. Start with your corporate goals and challenges; pick the metrics that align to those; determine the social media strategies that best deliver on those metrics; and execute!

As our investments in social media increase, so must the science and insightfulness of our metrics. Too many brands are merely counting things--fans, retweets, comments and likes--while ignoring the deeper and more meaningful measures of brand awareness, recall, consideration, association, preference and advocacy. Smart social media professionals do not settle for ineffective metrics but work to educate peers and leaders on the social media metrics that matter

for their brands.

STEP THREE: Be Honest

"Of all feats of skill, the most difficult is that of being honest."

- Comtesse Diane

Honesty sounds easy, but complete honesty can be surprisingly tricky. Honesty is not merely the absence of falsehoods; telling no lies in your social networks is only the starting point. Thorough honesty requires something more--more self-reflection, more care and more vigilance. It requires integrity and sometimes even courage.

Honesty requires a tenacious commitment to complete transparency. If you encourage people to tweet a photo of your product in return for a chance to win a prize, complete transparency demands those tweets be accompanied with a disclosure. It is one thing for consumers to choose to tweet their brand love with no expectation of reward (even if the brand solicits those recommendations), but if your brand creates the conditions where someone is motivated to promote your brand in order to win something, you must ensure transparency. It is deceptive to look the other way and allow consumers to be exposed to sponsored advertising communications without disclosure.

Honesty necessitates assertive vigilance to ensure that your employees, vendors and agencies are doing the right thing. It is not sufficient to assume your employees and partners know how to act with integrity, nor is satisfactory to set expectations and assume adherence. Honesty requires a commitment to education and engagement around ethics, and it demands that your brand supervises and monitors activities to ensure policies and regulations are followed.

Honesty demands sincerity in the intent of your communications. In paid media, brands communicate to persuade and sell, but in social media consumers expect something different from brands--it is a medium where consumers can choose to follow, comment and share, or they can choose to unfollow, block and ignore. Engagement should be earned with content that actually engages, not with tricks. For example, if you care to take a poll on Facebook, use Facebook's "Ask question" tool to do so; do not mislead your customers with fake surveys that request they "like" if they believe one thing or "share" if they believe another. Your intent with this sort of deceptive status update is not to engage consumers or learn from their answers but to manipulate Facebook's EdgeRank system. Honest relationships cannot be built with dishonest communications.

Honesty requires that you enter conversations to authentically join the conversation, not to co-opt the conversation. A new trend in social media is so-called "real-time marketing" (or RTM), where brands attempt to engage in the conversations consumers are having about sports, entertainment or world events as they occur. While it is possible for brands to post just the right thing at just the right time in a way that consumers will welcome, much of the recent RTM has been brazenly self interested and thus unsuccessful. The problem is that

brands have dishonestly attempted to inject advertising messaging into consumer conversations rather than trying to authentically express themselves or add value to those conversations. If your brand can bring value to the conversation, do so honestly, but if you just want to interrupt consumers' conversations with brand advertising, then stay silent honestly (or honestly pay for media).

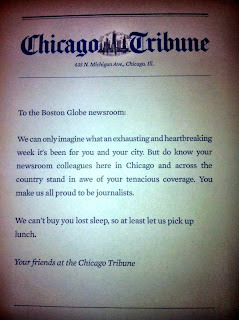

Honesty demands that you walk the talk. Consumers are so jaded about the way brands try to obfuscate their actions behind dishonest communications that an entire new lexicon has developed, including terms like greenwashing, astroturfing, sugging and flogs. Social media allows brands to chart a different course, not simply talking about how much they care but highlighting their care through real actions. At a time when some brands will hold their charitable donations hostage in return for likes, shares and replies, New Balance donated $1 million to the One Boston fund and did so without asking for a single "like." The actions of the Chicago Tribune went viral this week after the news organization sent pizzas to the Boston Globe newsroom along with a note that said news colleagues "across the country stand in awe of your tenacious coverage. You made us all proud to be journalists." The honest actions of New Balance and The Trib speak louder than any words could, and they are resonating honestly throughout social media. (How does Ford's branded expression of gratitude fare in comparison?)

Social media may feel quite mature, given that virtually every brand and the vast majority of people in the US have adopted social behaviors, but the medium is still very young. Social media professionals may understand today's best practices, but these continue to evolve as brands gain experience, laws and regulations change and the medium matures. In periods of rapid evolution, it can be difficult to discern the ethical from the unethical, but it starts with you. Ethical social media starts with ethical social media professionals--ones who consider the impact of their strategies, constantly challenge their own beliefs and are willing to stand up for what is right and not merely what is easy.

The idea that ethics comes from within rather than externally is not new. For support, I turn to a philosopher who died 2400 years ago and an animated insect. Aristotle believed self-knowledge was the key to individual ethics, and he wrote, “Knowing yourself is the beginning of all wisdom.” Jiminy Cricket, Pinocchio's sidekick, echoed Aristotle's advice, reinforcing that ethics starts from self-knowledge: "Always let your conscience be your guide."

Before you click "submit" to your next social media post, do not simply ask if it will achieve its goal, fits best practices and suits the brand. Ask yourself if it is honest, transparent and ethical. That is a much higher standard, but higher standards are what consumers want and what brands increasingly wish to deliver, aren't they?

A recent study by Contently found that "while a plurality (48 percent) of respondents believe that 'Sponsored Content' means that an advertiser paid for the article to be created and had influence on the article’s content, more than half (52 percent) thought it meant something different." The study further found that:

A recent study by Contently found that "while a plurality (48 percent) of respondents believe that 'Sponsored Content' means that an advertiser paid for the article to be created and had influence on the article’s content, more than half (52 percent) thought it meant something different." The study further found that:

%2B(2)%2B(537x800).jpg)

Instead of considering this in the abstract, let's examine two brands' actions last week, during the frightening events in Boston. NBC Bay Area posted a photo of a young bombing victim and implored people to "'Like' this to wish him a continued speedy recovery." This desperate attempt to trade on people's feelings for a young victim of the bombing in order to receive a bit of EdgeRank-building engagement is horrifyingly unethical, in my book. (And if you do not agree, then please tell me how "liking" an NBC post lends support to or otherwise helps this poor hospitalized child.)

Instead of considering this in the abstract, let's examine two brands' actions last week, during the frightening events in Boston. NBC Bay Area posted a photo of a young bombing victim and implored people to "'Like' this to wish him a continued speedy recovery." This desperate attempt to trade on people's feelings for a young victim of the bombing in order to receive a bit of EdgeRank-building engagement is horrifyingly unethical, in my book. (And if you do not agree, then please tell me how "liking" an NBC post lends support to or otherwise helps this poor hospitalized child.)

I am frequently disappointed to find social media professionals who do not understand the basics of ethics and regulation in the advertising industry. Marketing has a long and well established history of recognizing and enforcing ethical practices, and government regulation of advertising is over one hundred years old. The issues we struggle with today in social media marketing are not new, nor are the core beliefs of ethical marketing. The latter can inform the former for those who care to learn history.

I am frequently disappointed to find social media professionals who do not understand the basics of ethics and regulation in the advertising industry. Marketing has a long and well established history of recognizing and enforcing ethical practices, and government regulation of advertising is over one hundred years old. The issues we struggle with today in social media marketing are not new, nor are the core beliefs of ethical marketing. The latter can inform the former for those who care to learn history.

I've been invited to participate in a webinar about Ethics in Blogging, sponsored by SocialMediaToday.com and The Social Media Group. The event will occur Thursday, September 24th at 1 pm ET/10 am PT. You can register to listen and participate for free, and the event is a steal at that price!

I've been invited to participate in a webinar about Ethics in Blogging, sponsored by SocialMediaToday.com and The Social Media Group. The event will occur Thursday, September 24th at 1 pm ET/10 am PT. You can register to listen and participate for free, and the event is a steal at that price!