Tweet

While social media may today feel mature and fully integrated into our world, we have only seen the start of the changes social technologies and behaviors will bring to our personal and business lives. Profound evolution is coming that will alter how we operate our businesses, buy products, manage money, attain status and establish and protect our identity.

It is instructional to look at how the Web developed, because it provides a means to understand how nascent social media still is and how much change is ahead. In 2011, the number of US adults that use social media sites surpassed 50% for the first time. To put that into a historic perspective, the Web surpassed the 50% adoption mark in 2000. Now consider the amount of change the Internet has brought to business and our lives since 2000, and you get a sense for the substantial transformation that social media and social business will create in the next decade.

Some of the changes social media and social business will deliver will be welcome, but some of it not. After all, the Web brought many changes we all cherish (Free email! Real-time news! Videos of cats playing piano!) but many we do not (Connected to work 24/7; loss of privacy; online bullying). Exciting and difficult times are coming.

As my friend, Neff Hudson, likes to say, “There’s a lot of future in the past.” We cannot predict the future of social media and social business with certainty, but the trends and outcomes become much clearer as we compare and contrast the Web experience of the past 15 years to the social experience we can expect in the coming 15 years.

PHASE ONE: Businesses and Most People Pay No Attention

The Web: The advent of the Web was not the first time people used computers to communicate and access information on networks; Bulletin Board Systems had existed since the 70s and were hardly setting the world on fire. When Prodigy and AOL opened up the Internet to the public in 1995, the world greeted this momentous event with a yawn. Most people said they had no interest and found it dangerous; business dismissed the Web as a place for geeks and kids; and naysayers predicted people would never purchase $2,000 PCs and rewire their homes just to use the Internet. Still, some people recognized the trends and invested in the future; in 1995, while bookseller Borders sat confidently on hundreds of millions of dollars of investment in their retail stores, a guy named Jeff Bezos launched Amazon.com and sold his first book, “Fluid Concepts and Creative Analogies.”

Social Media: The advent of Friendster, Myspace and Facebook was hardly the first time people used the internet to connect and share; sites like Geocities and SixDegrees.com permitted people to update personal web pages and share connections, and these sites were hardly setting the world on fire. When Facebook opened its gates and became a public social network in 2006, the world greeted this momentous event with a yawn. Most people said they had no interest and found it dangerous; business dismissed Facebook as a place for geeks and kids; and naysayers predicted people would never embrace online social sharing widely. Still, some people recognized the trends and invested in the future. It is too early to tell who may be the Jeff Bezos of social business, but at a time when few people saw social media as a business platform, Shelby Clark started RelayRides, Chris Larsen launched P2P lender Prosper, Renaud Laplanche initiated LendingClub, and Perry Chen, Yancey Strickler, and Charles Adler created crowdfunding site, Kickstarter. (Only time will tell if these names are mentioned alongside Bezos' ten or fifteen years from now.)

PHASE TWO: Consumer Media Consumption Habits Change and Marketers (Slowly) Take Notice

The Web: In the late 90s, the Web was growing. Adoption was strong, particularly among younger consumers. Most in the business world still shrugged, but the Marketing Department took notice. The shift of marketing dollars into the online channel substantially lagged behind the shift of consumer online media consumption, but marketers cautiously began to invest in banner ads and search ads. Marketers also launched their companies’ first web sites, but they did not embrace the fundamental principles of this new medium. Early sites took the text and images used in existing print collateral and pasted them into static, non-functional Web pages, resulting in the term “brochureware” to describe the first generation of Web sites.

Social Media: In the late 00s, social media was growing, led by blogs, Facebook and Twitter. Adoption was strong, particularly among younger consumers. Most in the business world still shrugged, but the Marketing and PR Departments took notice. The shift of marketing dollars into the social channel substantially lagged behind the shift of consumer social media consumption, but marketers cautiously began to invest in blog advertising, sponsored conversations with bloggers, and Facebook advertising, with 70 billion display ads appearing on Facebook in the first quarter of 2009. Marketers and PR professionals also launched their companies’ first blogs, fan pages and Twitter profiles, but they did not typically embrace the fundamental principles of this new medium. Early blogs and social media profiles took existing press releases and pasted those social media sites, and some marketers treated blogs as they would paid media and were embarrassed when their efforts to buy their way to blog success were revealed, resulting in the term “splog” to describe spam blogs.

PHASE THREE: New Business Ideas Attract Investment Faster than Customers

|

| NASDAQ's two-year 188% dot-com climb |

The Web and e-Commerce: By the late 90s, a dot-com boom was underway. As early Web retailers like Amazon grew rapidly, the business world took notice and got scared. Old-line business worried that it was out of step with a “new economy” defined by clicks and users and not earnings per share, and investors feared they were missing something big and threw money at any entrepreneur with an online business idea. For example, dozens of online pet stores launched and competed to gain users quickly and at any cost; Pets.com raised $300 million of investment capital and bought expensive Super Bowl advertising in the land grab for new online customers. The focus of all this attention was not really on robust e-business but specifically on e-retail; Amazon and Pets.com sold physical goods, just like the book and pet stores on the corner, and most business leaders obsessed over how the internet would affect price, selection and delivery of existing products rather than on how it might create new products and services. Then in 1999, Sean Parker launched Napster and sent shockwaves through the music industry, demonstrating that the Internet was not just a medium to market and sell physical CDs.

Social Media and Social Commerce: A social media stock boom has and may continue to occur. As Facebook’s share of the display-ad market grew from 2% in April 2009 to 20% in April 2010, the business world took notice and got scared. Old-line business is worried it is out of step with a “new economy” defined by retweets and likes and not earnings per share, and investors fear they are missing something big and are throwing money at any entrepreneur with a social idea. For example, many group-buying and -discounting sites have launched and are competing to gain users quickly and at any cost; by the end of 2010, Groupon had turned down a $6 billion offer from Google, raised almost a billion dollars in venture capital and was buying expensive Super Bowl advertising in the land grab for new social customers. The focus of all this attention is not really on robust social business but specifically on social retail; Groupon and Facebook advertising are largely driving people into existing businesses like the book and pet stores on the corner (and to online retail sites) that sell existing products, and traditional retailers such as Gap and JCPenney launched early F-commerce stores on Facebook. While not as headline grabbing as Groupon’s, LinkedIn’s and Facebook’s IPOs, small peer-to-peer business companies are showing strong growth and demonstrating social media can be a medium for collaborative consumption and not just a medium to market and sell existing products.

PHASE FOUR: Stock Values Crash While Business Value Widens

|

| NASDAQ's one-year 63% dot-com crash |

The Web and e-Business: As it turned out, profits and earnings per share mattered. The dot-com bubble burst in painful fashion, destroying $5 trillion in market value between 2000 and 2002. The correction even caught the winners of the Web 1.0 era—after five years, Amazon had yet to make its first dollar of profit and could not build earnings quickly enough to justify its exorbitant stock price, and shares plunged from $107 to $7. Startups like Pets.com with weaker business models never made money and evaporated completely. However, what crashed were stock values and not the value of the Internet, and out of the ashes of the dot-com disaster grew something bigger and stronger. Consumers continued to adopt the web, broadening both the demographics and the use of the medium.

Online consumers had different expectations and demanded more—they wanted more product information, access to account information

and service in their channel of choice,

and they wanted it now. Online advertising and e-retail continued to grow, but something more substantial was happening—brochureware sites were replaced by rich, functional web sites, and the Web evolved from a focus on marketing and retail to a focus on business value throughout the enterprise.

Social Media and Social Business: I believe we are in the midst of a slow-motion social media market correction. Profits and earnings per share matter, and soon investors will care that Zynga and Groupon are struggling to attain and sustain profitability. Groupon is already trading near its all-time low price, almost half of its peak price five months ago, and a recent analysis demonstrated that just three of 2011’s twelve social IPOs were beating NASDAQ. I expect the social media bubble burst to be less painful because exuberance is not as great today as it was in 1999, but it still would not surprise me if the correction caught the winners of Web 2.0 era, causing Facebook’s post-IPO price to plunge as it struggles to build earnings quickly enough to justify its stock price. However, even as the market reconsiders the valuation of social media companies, something bigger and stronger is growing. Consumers continue to adopt social media, broadening both the demographics and the use of the medium.

Social consumers have different expectations and are demanding more—they want access to the objective opinions of other consumers, demand companies respond to their complaints posted to social networks and expect organizations to be more transparent about corporate practices,

and they want it now. The first F-commerce sites failed because they didn't bring true social benefits to the shopping experience, but social commerce can be expected to grow. In addition, advertising on social networks will explode as marketers continue to shift more dollars to the channel where consumers spend so much time. But, something more substantial than just social ads and retail is happening today—PR-oriented corporate social media profiles are being replaced by robust communities and dialog where companies engage consumers (and consumers engage each other) around business policies, service needs, new product ideas, employment, and more. Social media is evolving from a focus on marketing and PR to a focus on business value throughout the enterprise.

PHASE FIVE: Now It Gets Interesting: New Products and Business Models Challenge Old Ones

|

Estimated Quarterly US E-commerce Sales

as a Percent of Total Quarterly Retail Sales |

The Web and e-Business: For all the headlines and investor enthusiasm about e-retail in 1999 and 2000, the percentage of total US retail that occurs online did not surpass two percentage points until two years

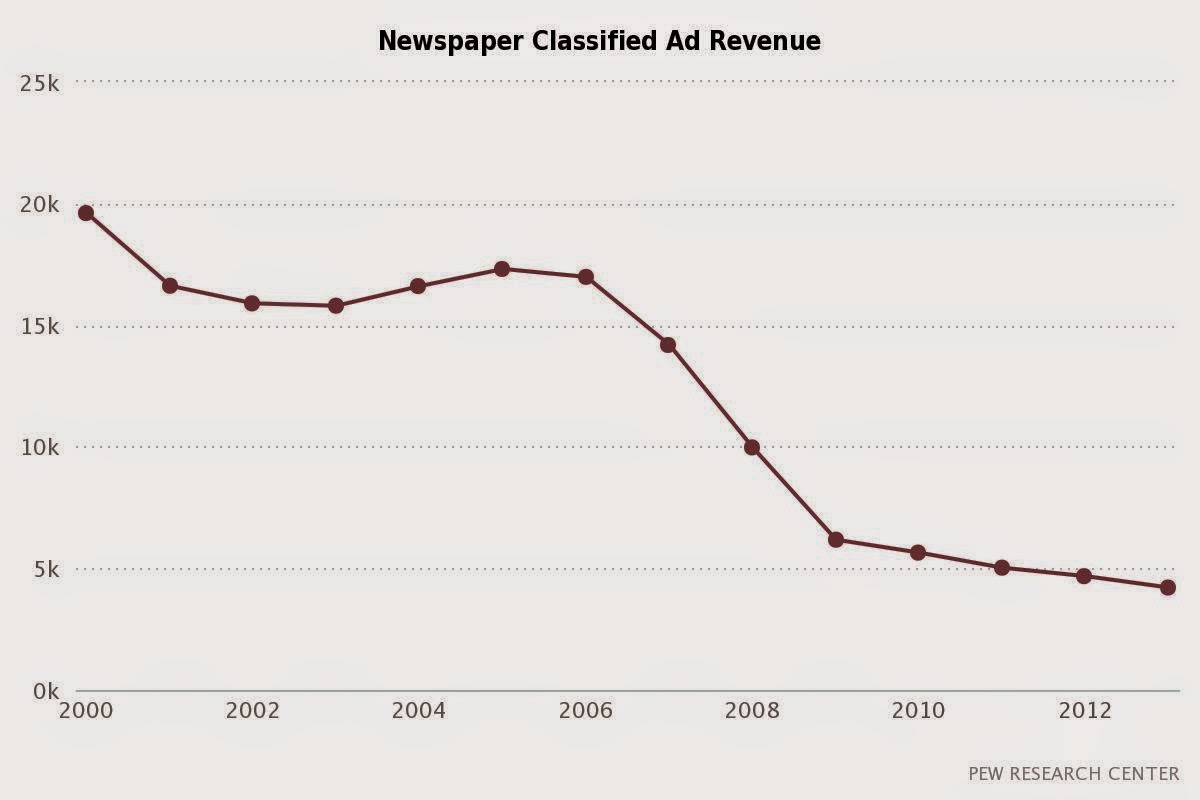

after the dot-com crash. Since then, the growth has been steady, but despite the fact online retail has shaken retail to its core and forced former powerhouses like Borders into bankruptcy, e-retail still represents just one of every twenty retail dollars spent in the US. Of course, online retail is wildly uneven, affecting some categories far more than others; digital sales of music surpassed physical sales just last year.

While the impact of e-retail has been significant, that is not the big story of this phase; rather, in recent years the Web has fundamentally changed consumers’ relationships with products and services. We used to buy CDs and listen to music in cars and at home—now thanks to iTunes, iPods and cell phones, folks download music and listen throughout the day. Many said they would never give up the joy of a paper book, but just a few short years after the creation of tablets and e-readers, one in five adults read an electronic book in the last year and Amazon already sells more e-books than print books. Mobile wallets, digital photography, real-time communications, online news, delivery tracking—the Web is no longer a way to market and sell traditional products but the foundation for completely new ways to conduct business.

Social Media and Social Business: Social media will bring great change to our products, services and business models over the next ten years, just as the web did in the last ten years. This won’t happen quickly—Amazon was selling books online for 16 years before e-books surpassed print books, and Napster demonstrated that consumers would download music 12 years before digital music sales exceeded physical ones. The companies that led these changes tended not to be the big, traditional, existing ones but the startups. Barnes and Noble has been remarkably nimble for an old-school organization, launching its first web site two years after Amazon.com and deploying the Nook two years after the first-generation Kindle, but today Amazon has diversified its business and enjoys a market capitalization more than 100 times greater than Barnes and Noble.

This trend repeated across categories—Kodak was too committed to print photography to lead in digital photography, and Apple handed the record industry its butt because it was unencumbered by physical music models. Today, for example, banks may be too invested in physical branches to lead in the social business space for financial services; no banks have launched or invested in peer-to-peer unsecured lending (Prosper and LendingClub), direct peer-to-peer lending between friends and family (National Family Mortgage) or alumni-to-student college loans. The nascent Sharing Economy and Collaborative Consumption models promise to change consumers’ relationship with products ranging from cars (RelayRides and Wheelz) to lodging (AirBNB) to lawnmowers and drills (Rentalic and NeighborGoods). Perhaps big companies will get smarter this time around—U-Haul has already launched a peer-to-peer model to finance the purchase of new trucks and GM has partnered with RelayRides.

PHASE SIX: New Technology Rewires People and Society

The Web: You might have thought Phase Five was the end, but the web has done more than just change products and services—it has altered consumers’ attitudes about themselves and the world. Our world is smaller, faster and more connected today than 15 years ago. We never want for communications or entertainment. We are never disconnected from our friends

or our jobs, no matter the time of day or day of the week. The web flattened corporate structures and altered organizational dynamics--business leaders are no longer protected by Administrative Assistants, work relationships are more casual and the speed and pressure of business have increased.

The Web made the world flat, instantly furnishing insight into happenings around the globe but also creating downward pressure on US salaries as outsourcing became exponentially easier. The Web put spectacular power into the hands of people, giving them the capacity to launch businesses, communicate widely and build reputation but also providing a platform for bullying, coordinating terrorist attacks and stealing identity. The Web has brought us together to raise record amounts of money for victims of earthquakes and tsunamis, but it has also furnished a way to drive us further apart as we reject news and information offered by a handful of media conglomerates and consume hyper-local, hyper-niche and hyper-partisan content.

The web has made parenting more difficult. Children grow up faster, can get themselves in more trouble, are exposed to more worrisome content and are impossible to monitor and protect as in the past. Parents cannot punish children by sending them to their room, because those rooms contain access to more information and entertainment than a TV network control room had three decades ago. Kids never have to negotiate for access to limited resources--homes that 15 years ago had one way to communicate externally and one screen for entertainment today have options too numerous to count. (Go ahead and try.)

The Web has affected how we go to school, date, work, age, retire and play. Absolutely nothing happens today that isn't caused by, planned, hosted, captured or shared on the Web. Without the Web, there would be no Tea Party or Occupy Wall Street, no multi-tasking, no telecommuting, no smartphones, no iPad, no World of Warcraft, no Angry Birds, and arguably no President Obama, Kim Kardashian, Lady Gaga, Justin Bieber or green movement.

Social Media: Social media has already affected communications in substantial ways, but the advent of peer-to-peer and sharing economy business models will do more than affect the communication networks we maintain. It will change:

- Our sense of identity: We are constantly connected to others, communicate in real time, and have more and stronger “soft relationships” (but some argue weaker “hard relationships”). Our identity is increasingly created not in quiet moments by ourselves but in constant and pervasive social interactions. A strong majority of Millenials say they are so connected they are never really alone.

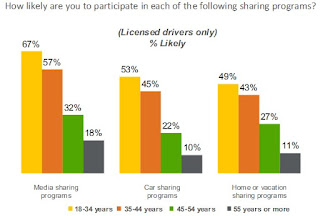

- Ownership: Already, many people rent music via a subscription model rather than buying and owning audio tracks, and over half a million people have used Zipcar’s 8,900 vehicles. This is not just changing the way we get products and services—it alters long-held attitudes. Teens are less inclined to get drivers licenses than in past in part because they are more open to public transportation and often choose to spend time with friends online rather than driving to see them. Cash-strapped consumers are finding they don't need to own certain categories of things, they only need to access, borrow and rent them in real-time.

- Status: As Collaborative Consumption rises, we will be defined less by what we drive, wear and own and more by our experiences and sharing—already more than half of Millenials agree with the statement “What I post online defines me.”

- Privacy: In the past we cherished our privacy, but in the future many will happily sacrifice privacy in order to gain access to sharing economy goods and services. We may soon elect to add our credit history and driving record to our online personas so that others will be more willing to rent us their cars, lend us money, allow us to stay in their spare room or rent us their hedge trimmers. Consumers will come under pressure to sacrifice privacy for transparency, but not because Facebook or some shadowy marketing research firm wants your data but because we will come to expect it of each other.

- Pricing: The more transparent we become, the more fluid prices will be—if you rent your car, would you charge the same to someone you can identify with a strong reputation, transparent credit score and open and clean driving record as you would to @HotGuy1992? Who we are, the trust we engender, the influence we create and our actions online won't just affect our access to sharing economy goods and services but also will influence the prices we are charged. The drive to earn our way to lower pricing with better behavior and more transparency will be a powerful force that encourages smarter financial decisions in the future.

We are just scratching the surface of the changes social technologies and behaviors will bring to our lives. For individuals, the future belongs to those willing to embrace both the welcome and difficult aspects of a more social, transparent world.

The same is true for business; the future belongs to those who see and invest in the future and not merely protect today's business models or chase this quarter's ROI. Amazon.com moved while others ignored the trends; it saw a business platform where others only saw retail and marketing; it invested for six years to achieve its first dollar of profit; and then it put its predominant revenue stream at risk with a bold new vision for how consumers would consume content in a digital and wireless world. Today, founder Jeff Bezos' personal wealth stands at $18 billion while the combined market caps of Barnes and Noble and Borders is just $730 million.

“There’s a lot of future in the past.”

.gif)